A number of years ago I received a call from a well-known individual in the community, informing me of an urgent meeting on a crucial issue. He pleaded with me to make every effort to participate, as my presence would mean a lot to those in attendance. I noted that my schedule for Thursday was already overloaded, but I would try to drop in.

Indeed, my commitments that day were back to back, ending with an evening lecture out in Long Island and the communal meeting slipped my mind.

As I drove through the streets of Flatbush Thursday night in a heavy deluge of rain, I turned down the street of the home where the meeting was taking place. As I rolled to a stop for the red light, I noticed an open door and recalled the individual’s imploration.

Truth be told, the hour was late and I was exhausted. All I wanted to do was to go home. But, feeling a sense of responsibility, I found a parking spot and ran through the downpour to the meeting.

A large crowd was in attendance. Three rows of seats extending the length of the house were filled with distinguished members of the community. I quietly took off my soaking wet coat and sat down in one of the empty seats in the back.

About a minute after I had taken my seat, the speaker’s voice thundered: “The reason nothing is happening is because of you. You could have made things work. I don’t know why you haven’t done anything.” He seemed to be addressing me.

In fact, he was staring directly at me. Then when he pointed his finger at me, there was no doubt that his remarks were meant for none other than me.

I was shocked. I had no idea who the speaker was, nor did I know to what he was referring. I contemplated what my reaction should be. I could stand up and indignantly protest my innocence. I could give him a piece of my mind for speaking out in public. Or, I could choose to remain silent. I didn’t want to protest as that could imply that there was some substance to his accusation. I was reluctant to reproach him because I was afraid of going too far. So I decided to remain quiet and suffer the abuse.

When the speaker’s tirade was over, I quickly picked up my coat and unobtrusively stepped towards the doorway. The host saw me go out, and ran after me in the rain. He assured me that there must have been some terrible mistake. He had no idea what the outburst was about and promised to expeditiously rectify the wrongdoing.

I thanked him for his concern and pleaded the lateness of the hour, contending that it had been a very long day for me.

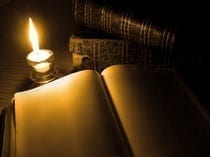

Although it was close to midnight when I arrived home, I began to look through my Torah books for a more profound explanation of what had transpired that evening.

I perused various divrei Torah on humiliation and embarrassment. Finally, in the wee hours of the morning, the table covered from one end to the other with sefarim(Torah books) , I found my answer. The Sefer HaSegulos tells us that if a person can withstand the nisayon (test) of public humiliation, and accepts the provocation with love, he will merit tovah gedolah, great benefit. Reading that I was comforted and able to go to sleep.

The next morning, as I walked into the house from morning prayers I heard the telephone ringing. I answered the call, and I immediately recognized the caller’s voice. It was the speaker who had verbally assaulted me the previous evening.

“Rabbi Goldwasser,” he pleaded, “I don’t have the words to apologize to you for last night. I feel horrible. I cannot even contemplate the enormity of my wrongdoing. How do I ask you for mechilah (forgiveness)? I thought you were somebody else. It was a case of mistaken identity.”

I could not deny the offense, and I replied, “I have already worked through the issue. The nisayon was my due and I have accepted it.

However, my question to you is, who gave you the right to publicly humiliate the individual for whom the insult was intended? Surely you are aware of the Chazal, “Hamalbin pnei chaveiro b’rabbim ein lo chelek l’olam haba” – “one who humiliates his friend in public doesn’t have a portion in the world to come.” The words that had been spoken could not be retracted, but I adjured him to ponder the significance of his misdeed and to always be mindful of every word he uttered. With that, we concluded the conversation.

Three years later I was invited to be the guest speaker at a gathering of a national organization. It was a major gathering attended by a large cross-section of Jews. As the chairman of the evening approached the lectern to introduce me, I was disquieted to see that it was none other than the speaker from that ill-fated communal meeting.

To my amazement, he began to recount the entire incident and confessed his personal implication in that evening’s verbal abuse. He then again asked for my mechilah(forgiveness) – this time in a public forum.

We learn (Yevamos 62b) that 24,000 students of R’ Akiva died in a plague during the period of Sefirat HaOmer because “shelo nahagu kavod zeh lazeh – they did not treat each other with proper respect.”

To expound on this concept, R’ Leib Minzburg cites the Talmud (Kiddushin 30b), “Even a father and son who study Torah become enemies of each other, yet they do not stir from there until they come to love each other.”

He explains that every individual learns Hashem’s Torah according to his understanding, and often cannot abide when someone else’s interpretation does not coincide with his, i.e. they become enemies of each other. However, it is not an animosity that is driven by ego or self-interest; rather, it is motivated by the desire to do Hashem’s bidding.

Yet, the ultimate objective is to learn together and discuss the differences, so that while one may maintain his opinion he can simultaneously appreciate and respect the other’s viewpoint as well.

Indeed, my commitments that day were back to back, ending with an evening lecture out in Long Island and the communal meeting slipped my mind.

As I drove through the streets of Flatbush Thursday night in a heavy deluge of rain, I turned down the street of the home where the meeting was taking place. As I rolled to a stop for the red light, I noticed an open door and recalled the individual’s imploration.

Truth be told, the hour was late and I was exhausted. All I wanted to do was to go home. But, feeling a sense of responsibility, I found a parking spot and ran through the downpour to the meeting.

A large crowd was in attendance. Three rows of seats extending the length of the house were filled with distinguished members of the community. I quietly took off my soaking wet coat and sat down in one of the empty seats in the back.

About a minute after I had taken my seat, the speaker’s voice thundered: “The reason nothing is happening is because of you. You could have made things work. I don’t know why you haven’t done anything.” He seemed to be addressing me.

In fact, he was staring directly at me. Then when he pointed his finger at me, there was no doubt that his remarks were meant for none other than me.

I was shocked. I had no idea who the speaker was, nor did I know to what he was referring. I contemplated what my reaction should be. I could stand up and indignantly protest my innocence. I could give him a piece of my mind for speaking out in public. Or, I could choose to remain silent. I didn’t want to protest as that could imply that there was some substance to his accusation. I was reluctant to reproach him because I was afraid of going too far. So I decided to remain quiet and suffer the abuse.

When the speaker’s tirade was over, I quickly picked up my coat and unobtrusively stepped towards the doorway. The host saw me go out, and ran after me in the rain. He assured me that there must have been some terrible mistake. He had no idea what the outburst was about and promised to expeditiously rectify the wrongdoing.

I thanked him for his concern and pleaded the lateness of the hour, contending that it had been a very long day for me.

Although it was close to midnight when I arrived home, I began to look through my Torah books for a more profound explanation of what had transpired that evening.

I perused various divrei Torah on humiliation and embarrassment. Finally, in the wee hours of the morning, the table covered from one end to the other with sefarim(Torah books) , I found my answer. The Sefer HaSegulos tells us that if a person can withstand the nisayon (test) of public humiliation, and accepts the provocation with love, he will merit tovah gedolah, great benefit. Reading that I was comforted and able to go to sleep.

The next morning, as I walked into the house from morning prayers I heard the telephone ringing. I answered the call, and I immediately recognized the caller’s voice. It was the speaker who had verbally assaulted me the previous evening.

“Rabbi Goldwasser,” he pleaded, “I don’t have the words to apologize to you for last night. I feel horrible. I cannot even contemplate the enormity of my wrongdoing. How do I ask you for mechilah (forgiveness)? I thought you were somebody else. It was a case of mistaken identity.”

I could not deny the offense, and I replied, “I have already worked through the issue. The nisayon was my due and I have accepted it.

However, my question to you is, who gave you the right to publicly humiliate the individual for whom the insult was intended? Surely you are aware of the Chazal, “Hamalbin pnei chaveiro b’rabbim ein lo chelek l’olam haba” – “one who humiliates his friend in public doesn’t have a portion in the world to come.” The words that had been spoken could not be retracted, but I adjured him to ponder the significance of his misdeed and to always be mindful of every word he uttered. With that, we concluded the conversation.

Three years later I was invited to be the guest speaker at a gathering of a national organization. It was a major gathering attended by a large cross-section of Jews. As the chairman of the evening approached the lectern to introduce me, I was disquieted to see that it was none other than the speaker from that ill-fated communal meeting.

To my amazement, he began to recount the entire incident and confessed his personal implication in that evening’s verbal abuse. He then again asked for my mechilah(forgiveness) – this time in a public forum.

We learn (Yevamos 62b) that 24,000 students of R’ Akiva died in a plague during the period of Sefirat HaOmer because “shelo nahagu kavod zeh lazeh – they did not treat each other with proper respect.”

To expound on this concept, R’ Leib Minzburg cites the Talmud (Kiddushin 30b), “Even a father and son who study Torah become enemies of each other, yet they do not stir from there until they come to love each other.”

He explains that every individual learns Hashem’s Torah according to his understanding, and often cannot abide when someone else’s interpretation does not coincide with his, i.e. they become enemies of each other. However, it is not an animosity that is driven by ego or self-interest; rather, it is motivated by the desire to do Hashem’s bidding.

Yet, the ultimate objective is to learn together and discuss the differences, so that while one may maintain his opinion he can simultaneously appreciate and respect the other’s viewpoint as well.

It was this aspect of the interrelationship that the students of R’ Akiva had not mastered. Although their intent was l’shem Shamayim (for the sake of Heaven), the inadvertent or misguided outcome proved to be deadly.

Many times in life, an individual’s motive for his offensive behavior is well-intentioned, even purely for the sake of Heaven, but once he disregards the other’s honor and respect he has overstepped the bounds of the Torah.

Informez votre médecin si vous prenez, avez récemment pris ou pourriez prendre tout autre médicament. Les informations sur les effets de l’alcool sont à la section 3. https://www.cialispascherfr24.com/ Si vous souhaitez plus d’informations, parlez-en avec votre médecin.

0 44 5 minutes read