Shavuos commemorates Hashem’s huge Revelation at Sinai, amid thunder, smoke and a voice heard by three million people. The Revelation was unmistakable, undeniable. It left its indelible impression on all the Jewish souls who stood on the desert sand around the mountain and on all the Jewish souls who would ever be born. Sinai was a once-in-history event, but throughout the ages Hashem discreetly discloses Himself in subtle intimations, phantasmagoric incidents and unlikely “coincidences.” When the earth trembles and fire flares up from the mountain, we know that Hashem is revealing Himself. But what about when a computer deletes an airline reservation and a pair of tefillin goes missing? *** Zevi* was three weeks after his 19th birthday when his father died. Nachum Wolstein, 52, was attending his parents’ anniversary party when he keeled over and was rushed to the hospital. The

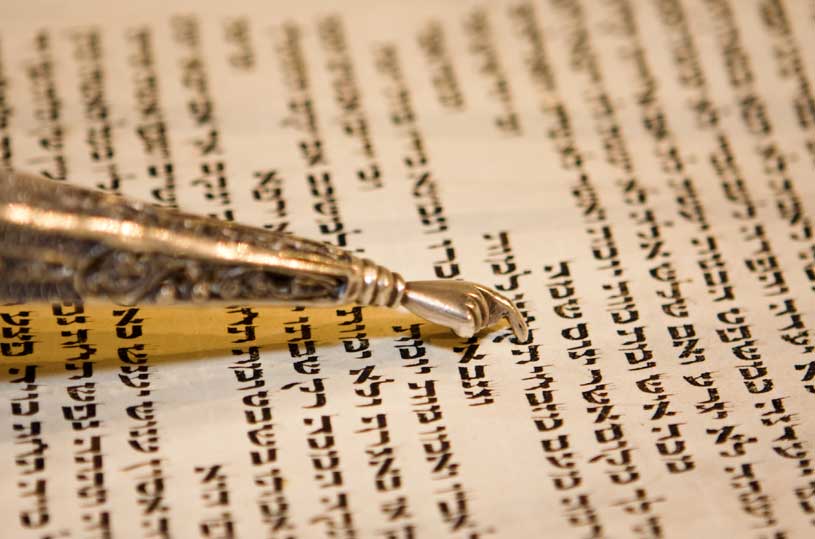

doctors managed to get his heart beating again. He lingered for 13 days, enough time for his wife, Leah, to summon Zevi home from Israel, where he was learning in the Mir. Every day Leah brought Nachum’s tefillin to the ICU, but the medical staff refused to let her put them on Nachum’s unconscious body, tethered as it was to wires and tubes. Zevi and his two older sisters sat by the bed day and night reciting Tehillim. On the morning of the thirteenth day, Nachum shed three tears—which Leah surmised were for his three beloved children—and returned his soul to his Maker. As the shocked and shattered family drove home from the hospital, Leah broke the tearful silence with an exhortation as pure as Sinai. She said to her children: “We are going to love Hashem as much tomorrow as we did yesterday.” Zevi stayed home for five weeks after the shivah. He told his mother that if she wished, he would drop out of the Mir and continue learning in Brooklyn.Leah wouldn’t hear of it. Zevi was a brilliant student, totally dedicated to his Torah learning. He belonged in Eretz Yisrael. She belonged in her house— alone. It was Tammuz.

As soon as Zevi left for Israel, Leah made a reservation for him to fly home for Pesach. Then he would stay in America; she didn’t have the money to send him back. Two days before the end of the winter zman, Zevi got a call from El Al. His flight to New York was overbooked. They asked him to agree to be bumped; in exchange they would put him on a flight changing planes in Frankfurt and give him a free ticket to return to Israel. Zevi had only one hesitation. He was saying Kaddish for his father. Where would he find a minyan in the Frankfurt airport? His nine apartment mates were also booked to fly to New York on El Al. He would agree to be bumped if El Al bumped all ten of them. The other boys were thrilled to get free tickets and to be part of Zevi’s traveling minyan for Kaddish.Three days later, the bachurim checked in at Ben Gurion Airport for their flight to Frankfurt. All went smoothly until it was Zevi’s turn. The computer had no record of his reservation. It was crazy, his friends insisted, because Zevi was the one who had gotten them this deal. The El Al agent summoned her supervisor, who told the other nine boys to proceed to the gate or they would miss their flight. Zevi never wasted time. While the agent and the supervisor were trying to solve the problem, he took a sefer out of his carry-on, sat down and started learning. He had no idea how much time had passed when the supervisor suddenly handed him two boarding passes and told him to follow her quickly to the gate. There was no time to take his carryon through security, she admonished him. He had to check it—and fast! Zevi hurriedly snatched his tefillin from the bag, and with his sefer in one hand and his tefillin in the other, he ran. The boys davened in the Frankfurt airport and Zevi recited Kaddish, amidst what they felt were dagger-like stares. When they reached JFK, Leah was waiting to pick up her son.

The next morning, Zevi told his mother that he must have left his tefillin bag in the car. He went out to fetch it. Ten minutes later, he came in looking distraught. “I lost my father,” he cried, “and now I’ve lost my tefillin.” He explained to her tearfully why the tefillin wasn’t in his carry-on, how he had been forced to check it and how he had held the tefillin in his hands during the layover in Frankfurt and all through passport control at JFK. With tortured sobs, he replayed his steps again and again. How could his tefillin have disappeared? With a calm clarity that surprised even her, Leah went upstairs, opened her deceased husband’s closet and took out his tefillin, which in the back of her mind she had intended to give to thegrandson born six weeks after Nachum’s death—the grandson who bore his name. Handing the tefillin to Zevi, she said, “For whatever reason we don’t understand, Tatty’s tefillin need to be worn now, and by you. They’re yours.” As soon as Zevi left for shul, Leah got into her car and drove to JFK. She inquired at El Al, at Lufthansa, at every lost-and-found. Desperate, she started searching through the trash bins in the arrivals terminal. The tefillin were nowhere to be found. A month later, Zevi returned to Eretz Yisrael with his father’s tefillin. Late one night, ten weeks after Zevi’s tefillin had disappeared, Leah’s phone rang. “Is this Mrs. Wolstein?” asked the male voice at the other end. “I think I may have your son’s tefillin.” The caller explained that he had been walking down Fifth Avenue that afternoon when a tall, turbaned Sikh approached him. He handed him a tefillin bag and said, “I think these belong to your people.” On the bag was embroidered only the first name, “Zev,” but inside there was a book.

When the Jewish man opened the sefer, he found the full name “Zev Wolstein.” Had Zevi not utilized those minutes in Ben Gurion Airport to learn, his tefillin would have been unidentifiable. The man went home, looked in the phone book and started calling all the Wolsteins. The first four didn’t answer. The fifth was Nachum Wolstein’s cousin, who gave the caller Leah’s number. Hanging up, a joyful Leah conjectured that Zevi must have left the tefillin bag in the upper compartment of his luggage cart at JFK. The next user must have inadvertently gathered up the bag with his own bags and put them in the trunk of a taxi. The Sikh man, who had identified himself as a taxi driver, must have discovered them in his trunk. But why did he wait ten weeks to find a Jew to return them to? Leah was eager to get the tefillin to Zevi as soon as possible, but because they had been in the possession of a non-Jew for ten weeks, she first took them to a sofer to be checked. By the time she got them back, her mother was preparing to leave for Eretz Yisrael the following week. Leah gave the tefillin to her mother, who delivered them to Zevi the day after she arrived. That day was the final day of Zevi’s reciting Kaddish for his father. The 11 months of Kaddish are the period when the soul is being judged in the Next World. The timing made Leah tremble. “Somehow,” she surmises, “my husband’s neshamah needed his tefillin to be worn by his son so that he would have menuchah in the Next World.” It was not the booming voice of Sinai, but to Leah and Zevi it was a whisper from Eternity.