One of the first mitzvoth of the Torah, the Korban Pesach – Paschal Lamb offering, was given to the Jewish nation as a preface to redemption.

Initially, it makes no mention of the command to eat it without breaking any bones. Only, some thirty verses later, when the Torah discusses the fundamentals of the offering, does it add that law, It adds it as a seemingly misplaced detail among serious edicts: such as who is permitted to eat it, and that the offering is a mitzvah which is incumbent on every Jew to partake.

“Hashem said to Moses and Aaron, “This is the chok (decree) of the Pesach-offering – no alienated person may eat from it. Every slave of a man, who was bought for money, you shall circumcise him; then he may eat of it. A sojourner and a hired laborer may not eat it.

Then it adds, “In one house shall it be eaten; you shall not remove any of the meat from the house to the outside, and you shall not break a bone in it. (Exodus 12: 43-45).

The question is: why insert the issue of broken bones, a seemingly minor detail, together with the fundamentals of this most important ritual? It seems out of place.

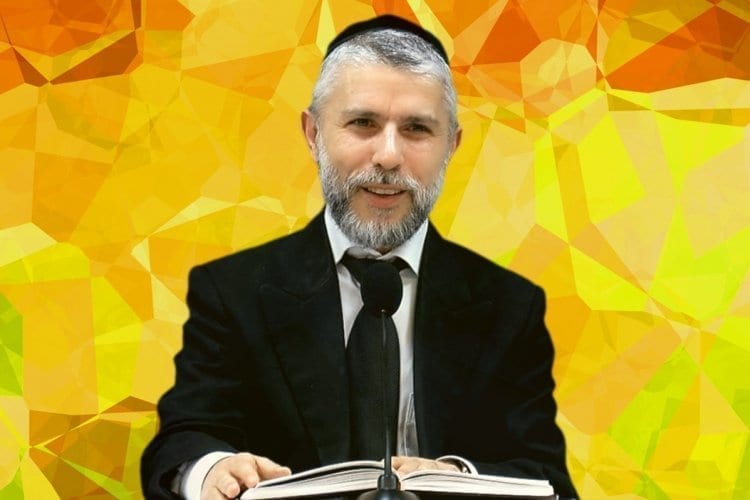

The Satmar Rebbe arrived in America after World War II ,along with a handful of Hungarian immigrants, who were his chasidim (followers) most of them Holocaust survivors. As is the custom, these chasidim would come for a blessing from the Rebbe, and leave a few dollars with him to give to charity on their behalf. Occasionally a wealthier chasid would leave a five, a ten, and sometimes a twenty-dollar bill. The Rebbe would never pay heed to the money placed in his palm; rather, he would open one of the drawers in his desk, stuff the money in, having it readily available for immediate charitable use.

Of course, charitable seekers of blessings were not the only ones visiting the rebbe. Those who were in need came as well, each of them bearing tales of sorrow and begging for financial assistance

One time a man entered the Rebbe’s chambers, with an urgent request for a few hundred dollars, which the Rebbe readily agreed to fulfill. The Rebbe opened his money drawer, and began pulling out banknotes. Out came a bunch of singles and several fives, a few tens and a twenty. He then called for his gabbai (assistant), “Here,” he said, please help me with this.”

The Rebbe began straightening out the bills one by one. Together, they carefully took each bill, flattening and pressing each one, until they looked as good as new. The Rebbe proceeded to organize one hundred one dollar bills and pile them in a neat stack. He then took out a handful of five-dollar bills and put them into another neat pile. Out came five wrinkled ten dollar notes; they too were pressed, and piled neatly as well.

Finally, the Rebbe bundled each pile carefully with a small rubber band, and then bound all the piles together with a larger band . He handed it to his gabbai, and asked him to present it to the supplicant. “Rebbe,” asked the gabbai; “why all the fuss? A wrinkled dollar works just as well as a crisp one!”

The Rebbe explained. “One thing you must understand. When one performs a mitzvah, it must be done with grace, and elegance. The way you give charity, is almost as important as the the charity itself. Mitzvot must be done regally, and with elegance. We will not hand out rumpled bills to those who are in need.”

The prohibition against breaking bones is not just a culinary exercise. The Sefer HaChinuch explains it is a fundamental ordinance that defines the very attitude Jews should have toward mitzvot. Though we might eat in haste – we must eat with class. We don’t break bones, and we don’t chomp on the meat – especially mitzvah meat.

A person’s actions while performing a Mitzvah is inherently reflective of his attitude toward the Mitzvah itself. The Torah, in placing this seemingly insignificant, command about the way things are eaten – along with the laws of “who is to eat it”, tells us that both the mitzvah and the attitude are equally important – with no bones about it!