“The lads grew up and Eisav became a man who knows hunting, a man of the field; but Yaakov was a wholesome man, abiding in tents. Yitzchak loved Eisav for trapping was in his mouth; but Rivkah loved Yaakov.”[1] Yitzchak loved his firstborn, Eisav, because “trapping was in his mouth”?! What does that even mean? And whose mouth are we discussing? Eisav’s mouth? Yitzchak’s own mouth? What would the phrase mean either way?

Rashi offers two explanations of the opaque phrase “for trapping was in his mouth.” According to his first explanation, the phrase is to be understood, “as Targum [Onkelos] renders it, ‘in the mouth of Yitzchak,’” for Targum Onkelos translates the phrase (into Aramaic) as “Yitzchak loved Eisav arei mitzeideih hava achil, because [Yitzchak] would eat of [Eisav’s] trapping.” The quickest way to a man’s heart…

Rashi, though, offers a homiletic interpretation, as well: the phrase “trapping was in his mouth” refers to “the mouth of Eisav, for [Eisav] would ensnare [Yitzchak] and deceive him with his words.”[2] Our Sages teach that Eisav would ask Yitzchak Avinu, “Father, how do we tithe salt and straw?” and as a result “his father would [thus] be under the impression that [Eisav] was meticulous about [the fulfillment of] mitzvos.”[3] Eisav’s question, however, was insincere, for tithes are taken only from fruits of the earth (and not salt) fit for human consumption (and not straw). As Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch states beautifully, Eisav “was a hunter also with his mouth; i.e., he employed the skills of a hunter even when he spoke. He knew how to use the tricks of his trade even against his father.”

So, either Yitzchak Avinu ate tasty meat and loved Eisav, or Eisav verbally toyed with Yitzchak Avinu…? If we were talking about deceiving Larry, Curly, or Moe, such a suggestion could be accepted; however, when talking about the saintly and spiritually lofty Yitzchak Avinu, that’s an untenable conclusion! Yitzchak Avinu was completely unaware of the actions of his eldest?! Our Sages teach us that, on the day Eisav’s grandfather – Avraham Avinu – passed away, “That scoundrel, [Eisav,] committed five sins… He had relations with a betrothed maiden, he murdered someone, he denied the fundamental belief [i.e., the existence of God], he denied [the doctrine of] the Resurrection of the Dead, and he belittled the birthright.”[4] With such a reprobate rap sheet, Yitzchak Avinu – who possessed ruach ha-kodesh – didn’t sense who Eisav really was, simply because he was served a delicious Delmonico?!

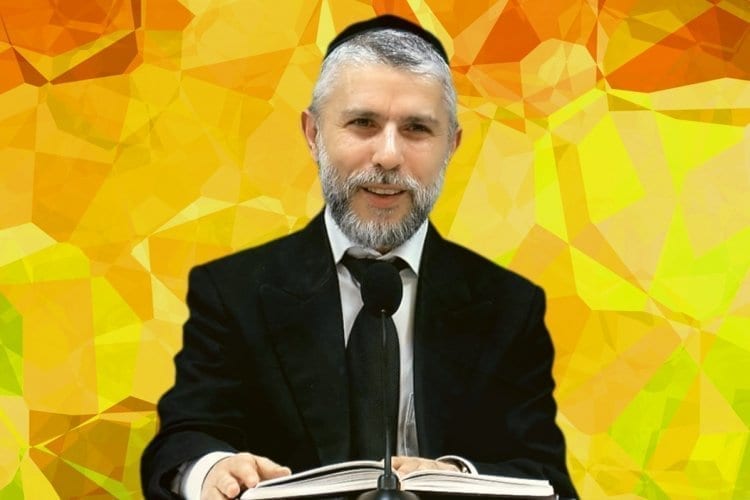

Rabbi Gavriel Toledano, the late rosh yeshivah of Yerushalayim’s Yeshivas Ohr Baruch (who passed away two weeks ago), offers[5] a beautiful explanation. The Midrash HaGadol, commenting on the aforementioned verse, notes:

As our Sages said, “Always, the left [hand] should push away but the right [hand] should draw close, [i.e. whenever one must rebuke another, he should not reject the other completely, but should hold out warmly the possibility of reconciliation].”[7] Therefore, the Torah says, “Yitzchak loved Eisav.”

Yitzchak Avinu knew exactly who his eldest son was, inside and out; however, the only way to possibly encourage Eisav to become who (Yitzchak Avinu knew) he could be was through loving him. At Eisav’s stage in life, there was no other way to educate and inspire him other than an outpouring of love. Yitzchak’s love was the only road that might lead to Eisav’s teshuvah. How, though, Rabbi Toledano asks, could Yitzchak love an adulterous, murderous, idolatrous, heretical ingrate of a son like Eisav? After anxiously awaiting children for so many years, how could Yitzchak feel love for this son of his?

The only way to love an Eisav-like child is to focus on the nekudah tovah, on a good quality – even if there’s only one – which the child possesses. Zeroing in on Eisav’s nekudah tovah was the secret to Yitzchak’s love. What, though, was Eisav’s nekudah tovah? The honor he showed his parents. “Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel said, ‘I served my father my entire life and yet I served him with less than one percent of the service the scoundrel Eisav showed towards his father.’”[8] Eisav’s extraordinary kibbud av va-eim must have been genuinely engrained in his neshamah; such devotion could not be faked, certainly not for an extended period of time.

Rabbi Toledano explains that Eisav must have had a deep-rooted appreciation for the spiritual purity that his father possessed. As such, whenever Eisav was with his father, he was inspired to greatness; however, the moment he stepped outside he could no longer maintain his righteousness. Nevertheless, “Yitzchak loved Eisav for trapping was in his mouth.” According to Rabbi Toledano, Rashi’s explanations mirror the two aspects of what Eisav’s nekudah tovah was. “Yitzchak loved Eisav arei mitzeideih hava achil, because he would eat of [Eisav’s] trapping,” i.e., Yitzchak’s love stemmed from Eisav’s nekudah tovah of kibbud av va-eim which manifested itself through Eisav’s preparation of tasty food for Yitzchak.

Alternatively, as Rashi noted, Yitzchak loved Eisav “for he would ensnare [Yitzchak] and deceive him with his words.” Rabbi Toledano innovatively understands that Yitzchak wasn’t actually deceived, despite Eisav’s attempts; however, Yitzchak could appreciate that when Eisav was around him, he felt a sense of inspiration to attempt to be more like his father, and posed questions (to the best of his ability) that reflected that inherent drive. That desire of Eisav’s was his nekudah tovah, which could function as the epicenter for Yitzchak’s love.

Parenting isn’t easy. Thankfully, your child – even on their worst day – isn’t as bad as Eisav; however, on those days when it feels like Eisav’s taken up residency in your child, focus on their nekudah tovah… maybe write it on a note and stick on the bathroom mirror, so you don’t forget.