The advent of Rosh Hashanah marks the beginning of the Aseres Yemei Teshuvah, the Ten Days of Repentance. This period ends at the conclusion of Yom Kippur.

However, the first two days, Rosh Hashanah, are markedly different from the last day, Yom Kippur. Among other distinctions, it is customary to eat festive meals on Rosh Hashanah, whereas on Yom Kippur we fast.

Additionally, there are a number of foods traditionally eaten at the beginning of the evening meal that are meant to be simanim, signs or omens, for an auspicious year to come.

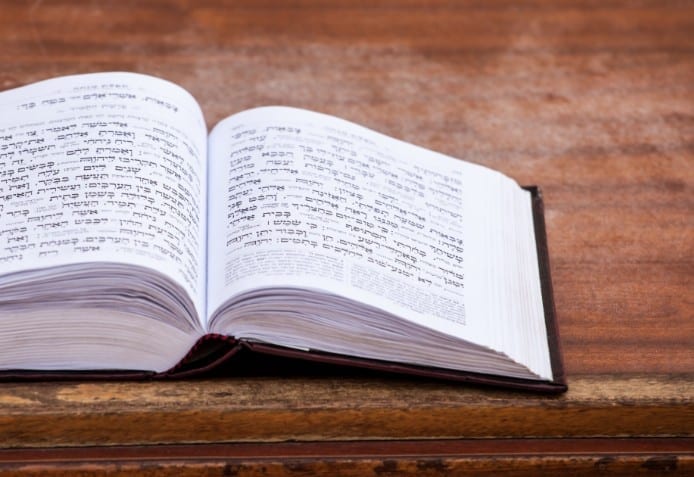

There are two passages in the Talmud that discuss the ritual of simanim. In each of them, Abaye enumerates five of these simanim and states that it is advisable to engage in this ritual on Rosh Hashanah in order to effect a favorable new year. There are, however, differences between the two passages.

The version in Maseches Horayos (12a) quotes Abaye as saying that the positive benefits are accrued merely by “looking” at these foods, while in Maseches Krisos (6a) the text quotes Abaye as saying that these foods must be “consumed.” A third variation is cited by the Ran, which involves “bringing” these foods to the Yom Tov table.

The Ran (commentary on the Rif, Rosh Hashanah 12b) relates that Rav Hai Gaon would have a basket of these various foods brought to the table, whereupon he would hold each item in his hand and recite an appropriate tefillah. While the Rambam ignores this ritual, it is our custom, based upon the ruling of the Shulchan Aruch, to eat the simanim as well as to recite the designated tefillos.

The Geonim question whether the minhag of simanim is a form of sorcery or divination, which the Torah expressly prohibits. To suggest that certain foods can influence our fortune in the coming year seems almost blasphemous.

The Meiri (on Horayos 12b) explains that the simanim do not, in fact, have any intrinsic power. The purpose of simanim is to merely awaken our hearts to repentance, the assured result of which will be a favorable judgment for a sweet and prosperous new year. In order to accomplish this, he explains, various tefillos were instituted to accompany each siman.

But how are we to reconcile the two Talmudic passages as to whether one is to merely look at the siman or actually eat it?

It appears that the two different versions parallel the two divergent opinions about whether one is obligated to feast or fast on Rosh Hashanah.

The Hagahos Maimoniyos (on the Rambam, beginning of Hilchos Shofar) cites the opinion of Rav Natronai Gaon that it is advisable to fast on Rosh Hashanah, as well as on Shabbos Teshuvah. He also records an opposing opinion of Rav Hai Gaon and Rav Nachshon Gaon, among other Geonim, that it is forbidden to fast on Rosh Hashanah. The version in Maseches Horayos, to the effect that one is supposed to look at these foods, corresponds to those who believe in fasting on Rosh Hashanah. The version in Maseches Krisos, which states that these foods must be “consumed,” is for those who eat festive meals on Rosh Hashanah.

Our present day custom of eating the simanim is derived from Rav Hai Gaon, whose opinion is that one is obligated to enjoy festive meals on Rosh Hashanah.

Rosh Hashanah is in effect steeped in contradictions. On the one hand, Rosh Hashanah is a Yom Tov, which would obligate one to have seudos. On the other hand, Rosh Hashanah is a day of prayer, judgment and repentance, which would obligate one to fast. A person is thus pulled in two opposite directions on Rosh Hashanah. How, then, can the two conflicting thrusts of this unique holiday be reconciled?

Chazal devised an ingenious resolution to this tension, by turning our meals into prayer rituals. We consume these various foods as entreaties and pleas for a sweet and prosperous new year. We thus eat, pray and engage in the act of repentance simultaneously.

The Ten Days of Repentance thus symbolize the process of repentance itself. At the very beginning, we are still mired in the animalistic side of our nature. On Rosh Hashanah, therefore, our prayers and penitence are intertwined with apples and pomegranates. As the process of teshuvah progresses, however, we become more and more purified, until on Yom Kippur we are likened to ethereal angels of G-d.