Hidden Within the Sin

Just as olive oil is hidden within the olive, so is teshuvah hidden within the sin itself. This is because, although repentance is one of the 613 commandments, one cannot repent unless he has sinned in the first place. Teshuvah, the possibility of repentance, is already hidden in its initial state of potential within the sin itself.

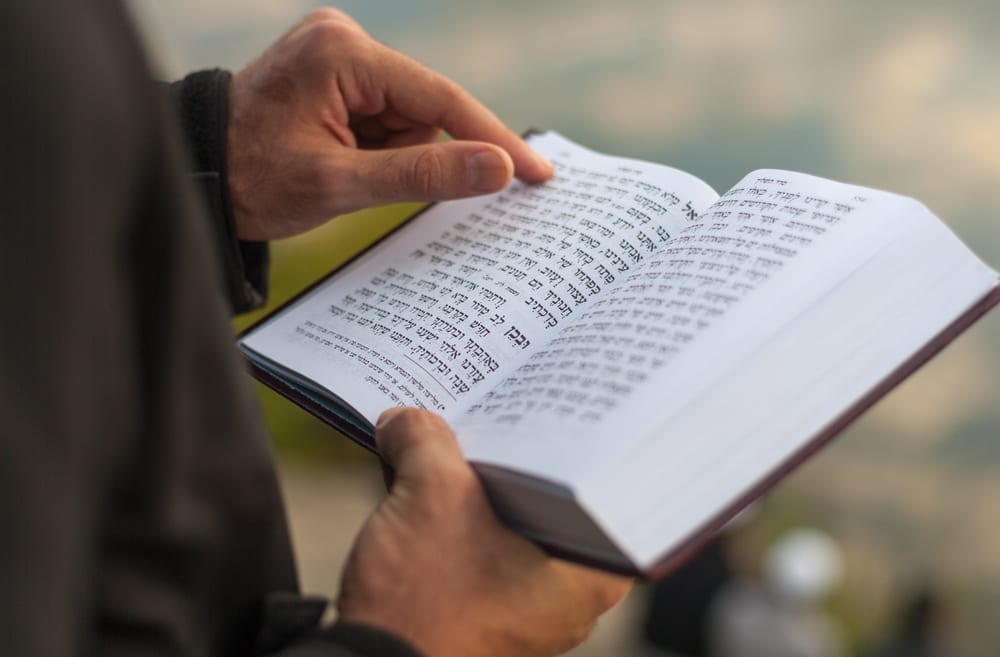

Likutei Amarim

Disguised as a Mitzvah

There are two types of people. One is truly wicked; he recognizes his Master and nonetheless rebels against Him. The other has been so blinded by his evil inclination that he and others around him are fooled into thinking that what he is doing is really good. They believe that he is a righteous Tzaddik. He might even study Torah and pray and afflict himself, but since he lacks true sincerity and faith in Hashem, his whole path is crooked and false.

The difference between the two is that there is hope for the truly wicked one. If he will one day pay heed to his feelings of remorse and does teshuvah wholeheartedly and beseeches Hashem for guidance, he can be saved.

The same cannot be said of someone who is fooled into thinking himself a Tzaddik! How can such a person ever do teshuvah when he does not even know that he is mistaken in the first place?

This is why, when the yetzer hara tries to seduce us into sinning, he tries to convince us that our misdeeds are actually mitzvos. This is a clever ploy — it prevents us from doing teshuvah over what we have done, because we don’t think we have done anything that requires repentance!

Ohr Torah

The Broken Egg

There are two types of sin: when a person transgresses the word of G-d and he knows it, and when a person is so full of himself that he thinks he is truly serving Hashem and doing mitzvos like a Tzaddik. When the first type of person encounters thoughts of repentance and feelings of regret, he does teshuvah. But not the second type! When he experiences feelings of remorse, he simply thinks more highly of himself for feeling this way, and his vanity only worsen. This effectively prevents him from doing teshuvah.

It is like the woman who was holding an egg and boasted to all who would hear her how this little egg was going to make her rich. “This egg will make me a wealthy woman,” she declared.

“First I will hatch it and raise the chick, and she will grow to be a chicken. Instead of slaughtering the hen, I will let her lay more eggs, and those eggs will also hatch, and soon I will have an entire coop of chickens laying eggs for me. I shall sell some of them and buy a calf and raise her to be a cow. Instead of slaughtering the cow, I will breed more calves until I have a herd, and then I will sell some of them and buy a field…”

As she went on and on, bragging and boasting, she dropped the egg and it broke, and so did all her foolish fantasies come to an end.

When we first begin to learn and we tell ourselves, “One day I will be a great scholar and a true chassid,” these vain fantasies are so full of arrogance that they cancel out any possibility of attaining true spiritual greatness from the outset.

Ohr Torah; Darkei Chaim

Hashem’s Pride in the Ba’al Teshuvah

There was once a king who had two sons. One son was faithful and dutiful toward the king. He could always be found at his father’s side. The second son was wayward and reckless. He could happily go for long periods of time without seeing his father more than once a week.

Eventually he grew so distant and rebellious that he took off and ran away. He disregarded his father’s deep, abiding love for him. Instead he blatantly shook off his father’s rule and decided to follow his own heart’s desires. He took up company with a band of vagabonds, thieves, and cutthroats.

The king could have sent armed guards after his son to force his return, but instead he exercised great mercy and restraint. Rather than punish his son, he pined after him and sighed longingly, “Woe is he who has exiled himself from his home and birthplace, and woe is the son who is not found at his father’s table!”

One day the wayward son came to his senses and regretted his ways. He recalled his father’s love and compassion and decided to return home. He would prostrate himself before his father, the king, and plead with him that he take him back.

And so he did. He prostrated himself and begged his father’s forgiveness. “Father,” he pleaded, “I have sinned and seen the error of my ways. Please forgive me!”

When the king heard his son’s earnest entreaties, the king’s compassion was roused and he took his son back. Seeing that his son’s remorse was genuine filled him with joy. Finally he had his son back, the one whom he had almost given up any hope of ever seeing again. He took pride in his son for returning of his own good sense and was filled with love for him, for returning out of love for his father.

The king’s affection and pride in the wayward son who had returned surpassed even those feelings he had for his dutiful son. He took the dutiful son’s obedience for granted since it had never wavered, but the sudden upsurge of emotions that he felt at being reunited with his lost son was much greater.

The king forgave his son completely and absolved him of all wrongdoing. He raised his once-wayward son in stature and gave him a station above that of all his brothers.

This parable, explains the Maggid, illustrates how Hashem feels differently toward the ba’al teshuvah than for the Tzaddik who has never sinned. Like the wayward son of the king, a wicked sinner who once turned away from Hashem evokes great pride and joy when he finally returns.

Ohr Torah